Representation is a key element in any visual design — you don’t want your brand to be represented by people who all look alike. Why, then, are white people so predominant in imagery all over the world, even though the majority of the world’s population is not white? Amy Gelera, AVP’s Visual Designer, has been delving into the matter in her Master’s Thesis and just might have some answers.

I was born in Guatemala in 1996. I was raised in Guatemala City and lived there until I reached 18 years of age. The country, like all of Latin America, currently finds itself within a complicated postcolonial web situated between faith and revolution. Now, I am a visual designer in Finland and a MA student in the department of Visual Communication Design at Aalto ARTS. I have been concerned, angered, intrigued and inspired by social issues — especially those that involve inequity on the basis of skin colour — since I was a child. While studying for my BA, I decided to voice my concerns about the lack of representation and consideration of humans outside the Western point of view through Graphic Design.

My family and I used to travel around the rural parts of the country quite often; my mum believed that a good way to shape the way I and my siblings viewed the world was to burst our middle-class bubble by better understanding the widespread situation of the country outside it. While taking a stroll through the department of Chimaltenango with my sister, we bumped into one of many decadent structures in the town of Santa Apolonia. This one was a kindergarten, quite a charming one. Despite its charm, all I could focus on was the small banner hanged above the door. It read ‘Kindergarden’ in big Arial letters, on top of a picture of what looked like a kindergarten. What caught my attention though, was why precisely this picture had ended up in this particular context: The picture displayed a group of white kids surrounding a table decorated with toys — and this in a town where there are very few white people. This image had been accessed through the internet, downloaded, edited, printed and finally situated here, in a country in which more than 41% of the population is Mayan.

The picture displayed a group of white kids surrounding a table decorated with toys — and this in a town where there are very few white people.

This particular situation made me recall how often I had experienced the same kind of mismatched visual scenario. I realised then that I, like many other residents, had gotten desensitised towards it while living in the city, since this is something that one encounters terribly often. Despite being taken aback by the initial shock of finding this specific image in such a remote place, I understood this was something that we — the inhabitants of the lands that were once colonized by the Europeans — had unwillingly accepted in our visual culture. Thus, quite tardily, I became aware that the usage of dogmatic western images from open-source image banks has become a granted standard of visual communication. And why wouldn’t it be? Like with many other shared postcolonial cultural aspects of Latin America, there is a clear yet systematically dismissed struggle between the glorification of western standards and the exploitation of that culture by the West. It is a difficult position to be in, and also a difficult context and history to fully understand.

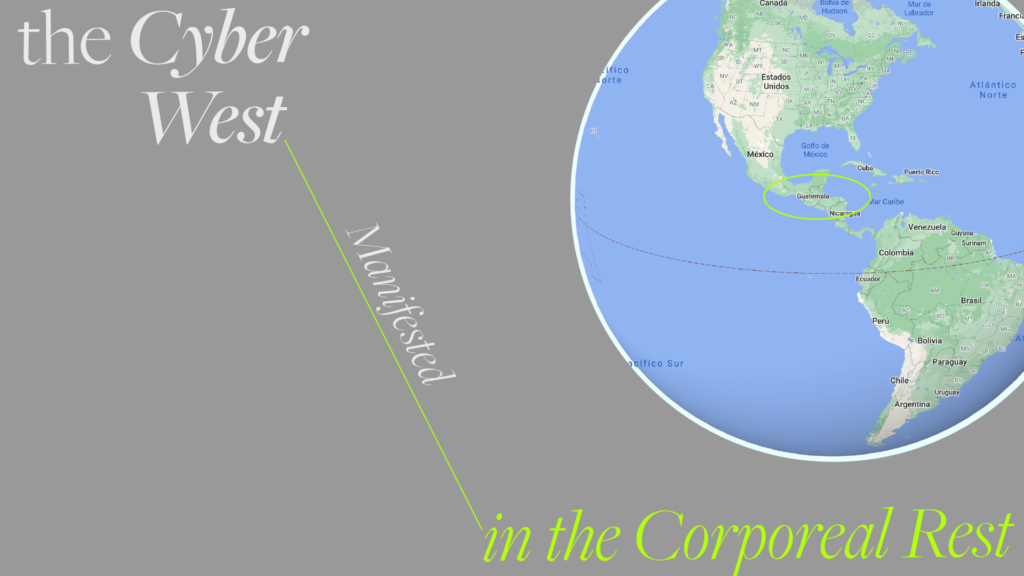

But I wanted to try. I started a journey to understand the phenomenon, because of which the glorified image of the West has become the most accessible and preferable visual element to use, flowing from open-source image banks to manifest itself physically in non-western contexts. It primarily appears as another postcolonial consequence derived from centuries of ethnic shaming and western glorification. However, it stems also from the fluid transnational nature of the colonized cyberworld and its relation to the physical world. So my first question was: How can graphic design approach a social and visual communication design issue that unravels between these two dimensions?

The glorified image of the West has become the most accessible and preferable visual element to use.

The Cyber West manifested in the Corporeal Rest is an ongoing MA thesis that searches to create a protest through graphic design against the invasion and colonization of visual culture fluctuating between open-source image banks and their manifestation in the tangible world outside of “the West”. This protest works towards the creation of a phenomenon against a phenomenon by building a perceptible movement that is communicated as an articulation against the present and the majority.